The French Past Perfect explained.

Jul 24, 2023Do you mix up your French have and had?

And does it blow your mind when you realise there are three ways to say HAD in French depending on what kind of verb is following it?

Well, join the heaving multitudes of people in the same boat. It’s the past perfect boat!

(Or the pluperfect . . . even the name varies!)

There are THREE ways to say ‘had’ in French to the English ONE!

Now, I like patterns, and both ‘have and ‘had’ are related. So I have set it out in a thorough video for you - a proper grammar mini-lesson for you.

In this mini-lesson, you’ll discover:

- What the past perfect is

- How this tense is constructed

- How the agreements work on the past participle

Nobody’s perfect!

Before we dive into our subject, let’s clarify something very important. Indeed, no one expects you to speak like a native speaker and have perfect pronunciation.

Have you ever been in a situation where someone asked you to repeat, not because it was bad but simply because you didn’t speak loud enough?

That’s natural. Since it’s not your mother tongue, you hesitate and the words barely come out of your mouth.

So, just relax, remember you are a learner and need to practise to improve. Do your best to enjoy the experience.

Besides, we all have a unique accent and that’s the beauty of it!

What is the past perfect?

Whenever you tell a story in the past, there are different actions in chronological order. If you started with a verb in the past (passé composé in French) and if something happened before it, you will use the past perfect.

The good news is this tense is always regular and works exactly like in English.

Here’s an example:

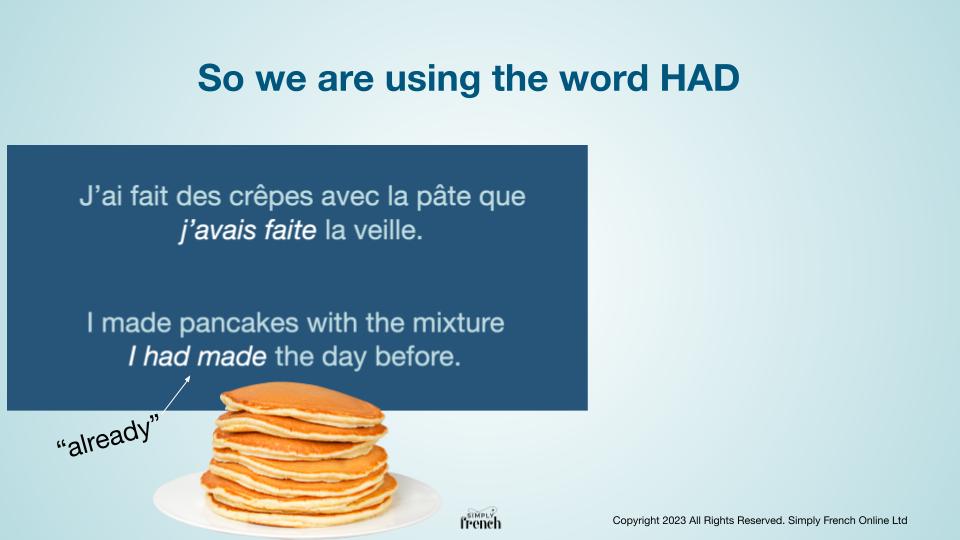

- J’ai fait des crêpes avec la pâte que j’avais faite la veille. >>> I made pancakes with the mixture I had made the day before.

This example is perfect for you to compare the same verb in the 2 tenses. The first one is with the passé composé (equivalent of present perfect) and the second one is the past perfect.

As you can see, the second part of your sentence is the first action or the one the most remote in time… That’s why we have to differentiate them.

The French past tenses on a timeline.

I have a timeline to help you visualise the different tenses. The past perfect happens before the perfect tense (passé composé in French).

In other words, the pluperfect is the past of the past.

The past perfect is the most remote past tense.

So, how do you conjugate the past perfect? Remember that I told you it’s similar in English.

Indeed, in English, the most remote tense in the past is the past perfect and its structure is: had + past participle.

Well, in French, the equivalent of “had” is your French verb “avoir” using the imparfait.

I have this video for you.

As a reminder, here’s how we conjugate “avoir” using the imparfait.

- J’avais

- tu avais

- il / elle avait

- nous avions

- vous aviez

- ils / elles avaient

This is just the first part of your tense. In the following section, let's take a peek at the auxiliary …

How to use the auxiliary in French.

Normally, you would have come across the passé composé before studying this mini-lesson. Why? Because both of them: the present perfect and the past perfect follow the same pattern. They both have an auxiliary and a past participle.

So, what’s the difference?

Well, the difference lies in the tense of the auxiliary. For the present perfect, the present is required while the past is for your past perfect.

Let’s have a look at these examples:

- (Present perfect) J’ai fait des crêpes. >>> I’ve made pancakes.

- (Past perfect) J’avais fait des crêpes. >>> I had made pancakes.

Therefore, as long as you master the passé composé, the past perfect will be a piece of cake! Indeed, you’ll need to focus on the past of the auxiliary.

How to conjugate your auxiliary for your French Past Perfect.

So, how do you actually conjugate the auxiliary?

Remember that you have the choice between the 2 auxiliaries that exist: “avoir” (to have) and “être” (to be) and another version.

Once, you conjugated your auxiliary, you will add the past participle.

With the verb “avoir” you obtain the following:

- J’avais

- tu avais

- il / elle avait

- nous avions

- vous aviez

- ils / elles avaient

With the verb “être” you have this:

- J’étais

- tu étais

- il / elle était

- nous étions

- vous étiez

- ils / elles étaient

With a reflexive verb (the action is on yourself), it works with “être” and you get this:

- Je m’étais

- tu t’étais

- il / elle s’était

- nous nous étions

- vous vous étiez

- ils / elles s’étaient

Here are some past participles for you:

- eu >>> had

- mangé >>> eaten

- vu >>> seen

- lu >>> read…

In the following section, see how to choose between the 3 options.

Which auxiliary should you use?

Oui, you’ve seen how to conjugate the 3 alternatives but how do you know which one to pick?

The answer is to ask yourself the right questions.

1) Is the verb reflexive?

One way to know it is if you see “se” with an infinitive like “se marier” (to get married), “se lever” (to get up)...

Thus, if it’s reflexive, you choose the auxiliary “être” and you don’t forget your pronoun before it otherwise it will be a normal verb with the same auxiliary.

- Je m’étais levé. >>> I had got up.

2) Is the verb an “être” auxiliary verb?

We focus on them in the following section. Basically, you should check if your verb belongs to this exclusive list.

Let’s see with the example of the verb “aller” (to go):

- J’étais allé. >>> I had gone.

3) Use “avoir” with all the other verbs!

Any French verb that is not reflexive nor in the list of “être” will work with the auxiliary “avoir” like the following:

- J’avais vu. >>> I had seen.

The specific verbs with the auxiliary “Être”.

So, what are these special verbs on your list of “être” verbs? They are mainly verbs of movement. In total, this list hahs 16 verbs.

A mnemotechnic will help you memorise: Dr.Mrs. VANDERTRAMP.

Let’s decipher this list together:

D : descendre >>> go down

R : rester >>> stay

M : mourir >>> die

R : retourner >>> go back

S : sortir >>> go out

V : venir >>> come

A : arriver >>> arrive

N : naître >>> be born

D : devenir >>> become

E : entrer >>> enter

R : rentrer >>> go back

T : tomber >>> fall

R : revenir >>> come back

A : aller >>> go

M : monter >>> go up

P : partir >>> leave

Thus, with these verbs, the auxiliary “être” is required. Then, follows its past participle:

D : descendu

R : resté

M : mort

R : retourné

S : sorti

V : venu

A : arrivé

N : né

D : devenu

E : entré

R : rentré

T : tombé

R : revenu

A : allé

M : monté

P : parti

What the auxiliary “Être” triggers.

Since you are familiar with the list of “être”, there’s an extra step you need to know.

Whenever you play with the auxiliary “être”, you should always be careful with the changes involved.

Indeed, if the subject is feminine, an extra “e” is necessary, and if it’s plural an extra “s”.

Let’s update the list this way:

- D : descendu (e) (s)

- R : resté (e) (s)

- M : mort (e) (s)

- R : retourné (e) (s)

- S : sorti (e) (s)

- V : venu (e) (s)

- A : arrivé (e) (s)

- N : né (e) (s)

- D : devenu (e) (s)

- E : entré (e) (s)

- R : rentré (e) (s)

- T : tombé (e) (s)

- R : revenu (e) (s)

- A : allé (e) (s)

- M : monté (e) (s)

- P : parti (e) (s)

With concrete examples, you’ll see this:

- Elle était partie à 16h00 >>> She had left at 4 PM.

- Ils étaient venus en avion >>> They had come by plane.

- Elles étaient restées à Marseille >>> They had stayed in Marseille.

You can also add 'passer' to this list - to call by someone's place.

What happens with reflexive verbs?

As mentioned before, the same applied to reflexive verbs. Let’s play with a few examples:

- Elle s’était maquillée avant de sortir >>> She had put some makeup on before going out.

- Ils s’étaient amusés en Corse >>> They had fun in Corsica.

- Elles s’étaient couchées à minuit >>> They had gone to sleep at midnight.

The exception to the rule.

I told you the agreement (addition of extra letters) works with the auxiliary “être” but it also works with “avoir” on one condition: if the object is before the verb.

Let’s compare these two examples:

- J’avais fait des crêpes. >>> I had made pancakes.

Here, nothing happens because the object “crêpes” is after the verb. However, things change in this version:

- Les crêpes que j’avais faites . >>> The pancakes I had made.

Clearly, the object “crêpes” is before the verb and it requires an agreement.

Basically, with the auxiliary “avoir”, double check if the subject is before or after your verb to make the changes.

To summarise, the past perfect is the past of the past or the most remote tense in the past.

It is very similar to the passé composé as far as the pattern is concerned: an auxiliary and a past participle.

For the past perfect, the auxiliary is based on the imparfait (pluperfect).

Then, to choose your auxiliary ask yourself the basic questions: reflexive? list of “être”?

Don’t forget the agreement if it’s feminine and plural and check if the the object is before the auxiliary “avoir”.

As long as you follow the steps one by one, you will be fine because the past perfect is a regular tense with no exceptions!

But, if you still have questions, please contact me!

Free Masterclass

Learn my 4 step method of how to hold meaningful french conversations the R.E.A.L. way in just 30 minutes a day.

When you signup, we'll be sending you weekly emails with additional free content